How would millions of Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza respond to the claim that, in Israel’s early years, Arab states effectively betrayed their Palestinian brethren, reaching informal understandings with the young Jewish state that enabled the mass immigration of hundreds of thousands of Jews? These new arrivals would not only bolster Israel’s military and economy but would also settle on lands abandoned by Palestinians in 1948.

This radical thesis is presented by historian Esther Meir-Glitzenstein in her new book, The Jews of Iraq: A Long History in the Land of the Tigris and Euphrates (Yad Ben-Zvi Publishing). Meir-Glitzenstein is a professor emerita at Ben-Gurion University and the daughter of an Iraqi-born mother.

Her academic work spans from the sixth century BCE to later immigration waves, including those from Yemen. But the story of the Iraqi Jewish immigration to Israel in the early 1950s is particularly dramatic. It reveals not only how Arab regimes abandoned the Palestinian cause but also challenges the traditional Zionist narrative surrounding the immigration of Jews from Arab countries.

In 1950, around 130,000 Jews lived in Iraq. Within just 20 months, at least 125,000—about 95 percent—immigrated to Israel. While more Jews eventually came from Morocco, that process took many years. The rapid and near-total departure of Iraqi Jews raises several questions about the government’s role: Who allowed them to emigrate? Did the Iraqi regime “hate” them, and were they merely fleeing persecution? What role did the Israeli government play in facilitating the exodus?

The Arab-Jewish conflict in Palestine became central to Middle East politics in the 1920s, and especially in the 1930s and 1940s. As tensions escalated, so did Arab leaders’ rhetoric. In 1945, the Arab League was established, and one of its first resolutions warned against the creation of a Jewish state and the harm it would bring to Arab residents of British Mandatory Palestine. League leaders even threatened that Jews in Arab countries would become hostages and pay the price for “Zionist aggression.”

On May 15, 1948—one day after Israel declared independence—Arab armies invaded, including troops from the Kingdom of Iraq. Within weeks, Israel had formed the IDF, and a year later, the War of Independence ended in a decisive Israeli victory.

But contrary to what one might expect, the Iraqi defeat did not spark anti-Jewish violence. “The authorities did not allow any attacks on Jews,” Meir-Glitzenstein says. “Events like the Farhud pogrom of the early 1940s, which occurred during a period of political anarchy, simply did not happen this time.”

3 View gallery

Nuri al-Said, prime minister of Iraq in the 1950s

(Photo: Arthur Tanner / Fox Photos / Getty Images)

She explains that the Iraqi government feared that any violence against Jews could spark nationalist unrest from opponents of the regime, who might use the chaos to overthrow the monarchy. Iraq was formally independent but heavily reliant on British support, and its political foundations were fragile.

This does not mean the authorities suddenly became pro-Israel. On the contrary, they targeted wealthy Jews with dubious accusations, sent them to prison and even executed some, most notably Shafiq Adas, a Jewish millionaire accused, without evidence, of selling weapons to Israel. “At the time, hundreds of members of the Haganah militia were active in Iraq,” Meir-Glitzenstein notes. “But the government’s actions, though harsh, focused mostly on wealthy elites and largely left these operatives untouched.”

Still, Haganah leaders feared the network could be exposed and launched, with the help of Mossad LeAliyah Bet—a Haganah branch—a smuggling operation to Iran.

This smuggling route infuriated the Iraqi authorities. It destabilized the border with Iran, fueled foreign currency smuggling and undermined the government’s leverage over the Jewish community. In response, Prime Minister Tawfiq al-Suwaidi introduced a drastic measure: a new law empowering the cabinet to revoke the citizenship of any Jew who chose to leave Iraq permanently, after signing a formal declaration before an Interior Ministry official.

According to Meir-Glitzenstein, the law was not designed as an expulsion measure. The government believed it could use legal emigration to rid itself of a small group of dissidents—communists, Zionists and smugglers. But reality quickly shattered this assumption.

Within a few months, 70,000 Jews had registered to give up their citizenship. Four months later, the number rose to 86,000. In total, 105,000 Jews—an overwhelming majority of the community—signed up to leave. The political crisis now landed on the desk of a new (and old) prime minister: Nuri al-Said.

What should Iraq do with this massive Jewish population?

Al-Said embarked on a diplomatic tour of the Middle East, trying to persuade neighboring states to absorb Iraq’s Jews. They all refused, insisting the issue was Iraq’s to solve. Unexpectedly, al-Said decided not to reverse the law or stop the exodus. Instead, he allowed—informally and discreetly—a mass Jewish immigration to Israel.

Did he sign an agreement with Israel?

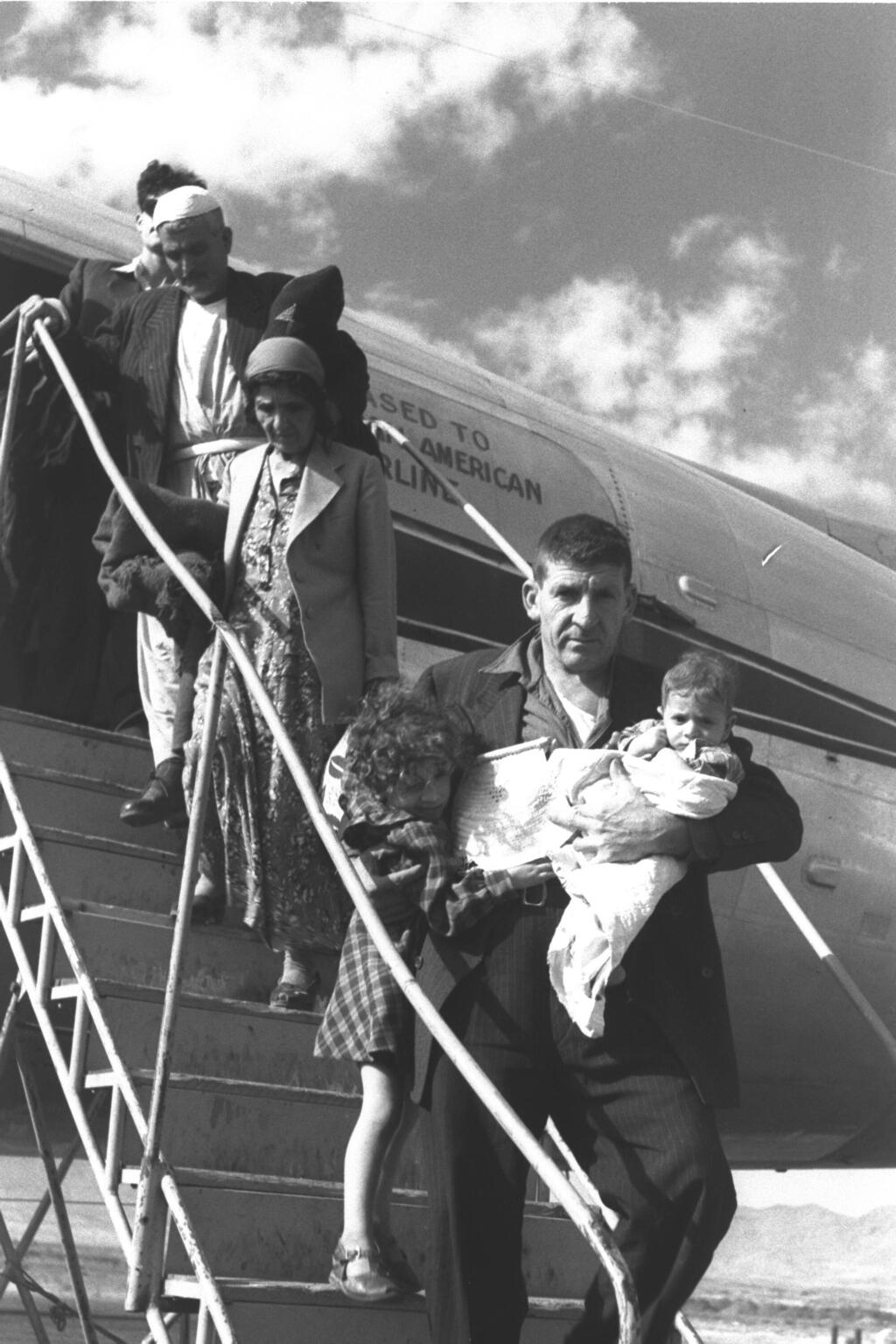

“Of course not,” Meir-Glitzenstein says. “But at the time, two representatives of the American commercial airline Alaska Airlines appeared in Iraq. They were Israeli emissaries: Shlomo Hillel (later Knesset speaker and government minister) and Ronnie Barnett, a British-Jewish pilot. They negotiated with the Iraqi government to fly Jews out of the country. Alaska—still a functioning U.S. airline—was a front for Israel’s El Al.”

Under the agreement—also supported by the British, as declassified documents show—the flights didn’t go directly to Israel but to Cyprus, then a British colony. Iraqi officials knew full well that Hillel, Barnett and Alaska were Israeli proxies and that Cyprus was just a transit point. But for al-Said, the deal had two advantages: he rid himself of a potentially subversive minority and confiscated a significant portion of their assets for the state treasury.

How did al-Said justify this to the Arab world?

“Cleverly—but not convincingly,” Meir-Glitzenstein says. “He claimed the influx of Jews would collapse Israel’s economy. That was far from true. Yes, Israel was in a difficult financial state, but it was not on the verge of collapse. If Israeli leaders had believed that more immigrants would harm the economy, they wouldn’t have brought them.”

Iraq wasn’t alone in enabling Jewish immigration—and, by doing so, undermining the Palestinian cause. Libya, under British control until its 1951 independence, also allowed tens of thousands of Jews to emigrate to Israel. In Yemen, in early 1949, Jews who had been living in refugee camps in Aden were permitted to leave, and by April, the Imam, Ahmad bin Yahya, announced that Jews could depart.

Syria, by contrast, completely sealed its borders. After gaining independence from France in 1946, it barred Jews from leaving—restrictions that remained until the 1990s. “Syria is an example of a state that actively chose to block Jewish emigration,” Meir-Glitzenstein says. “This proves it was possible to stop it. The fact that Iraq, Yemen, Libya and Morocco didn’t—and in some cases encouraged it—demonstrates their abandonment of the Palestinian narrative.”

Why don’t Palestinians talk about this today?

“I suspect it’s simply too uncomfortable for them,” she says. Discussing internal betrayal during one of the darkest chapters in their history isn’t something they’d want to highlight. Despite my research, I found no significant Palestinian criticism of these events. Even in the memoirs of the Iraqi prime minister at the time, the episode is mentioned only in passing. He, too, clearly preferred not to memorialize this dual reality: public declarations of support for the Palestinians, even military action against Israel, alongside legislation that knowingly enabled Jewish immigration to Israel—immigration that strengthened the Jewish state demographically, militarily and territorially.”