"I don’t miss Damascus at all. There’s nothing there. The only thing left there is the land itself. I don’t feel connected to the land – just to my roots and the values with which I was raised in the Syrian Jewish community," says Isaac Assa, a leading figure in Mexico City’s Syrian Jewish community. How did Jews from Syria end up in Mexico anyway? To answer this, we need to take a step back in time.

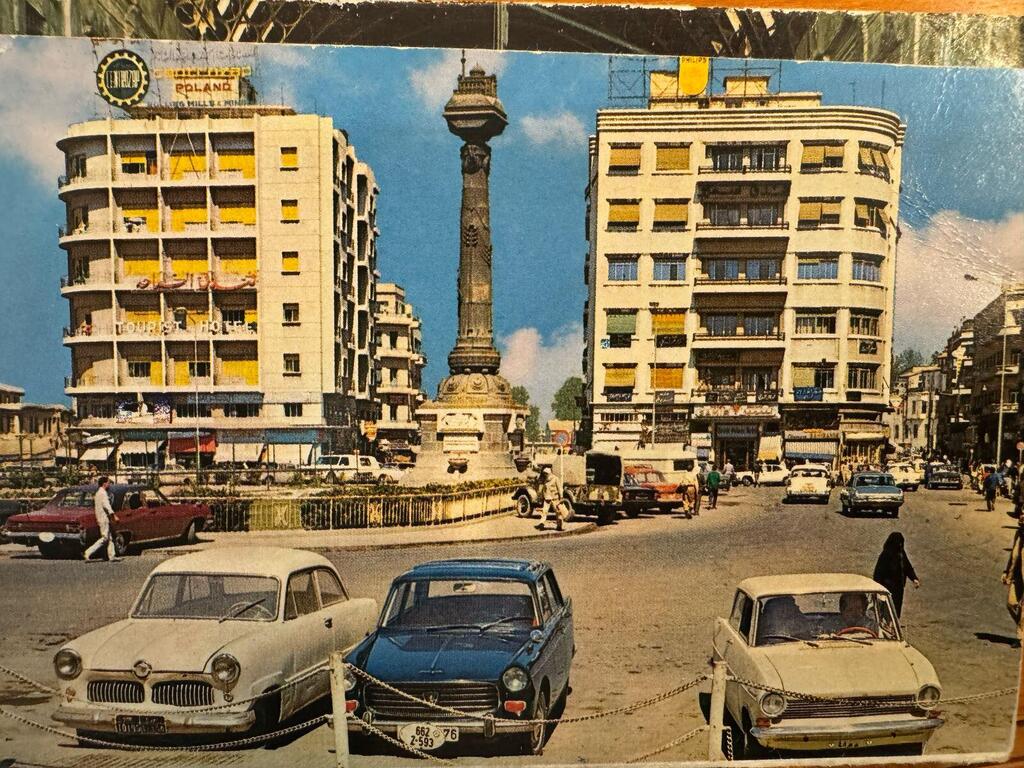

Estimates suggest that before the First World War, the Jewish community in Syria, primarily concentrated in Aleppo and Damascus, numbered around 40,000. Prof. Eyal Zisser of Tel Aviv University’s Department for Middle Eastern and African History, says there is evidence of Jewish presence in what is now Syria dating back to the Seleucid period in the fourth century BCE. Some Jews did manage to emigrate before the establishment of the State of Israel. By 1948 there were 30,000 Jews still remaining in Syria.

The Zionist movement and Israel’s War of Independence meant that the Jews in Syria, as in many other Arab countries, found themselves in a rather precarious situation: On the one hand, they felt a sense of commitment to the country in which they lived alongside their Muslim neighbors. On the other, a deep connection to Israel and Zionist sentiments.

"Before the conflict and Zionist activity, one could say that the treatment of Jews in Syria was reasonable," says Prof. Zisser. "They benefited from being a relatively small community of 40,000 out of a total population of 2 million. Yes, there were tensions and incidents that did occur, but Jewish life was manageable, and the treatment was in no way openly hostile. Things started changing for the worse in the 1940s primarily amid Zionist efforts and the UN partition plan, and later, the establishment of Israel."

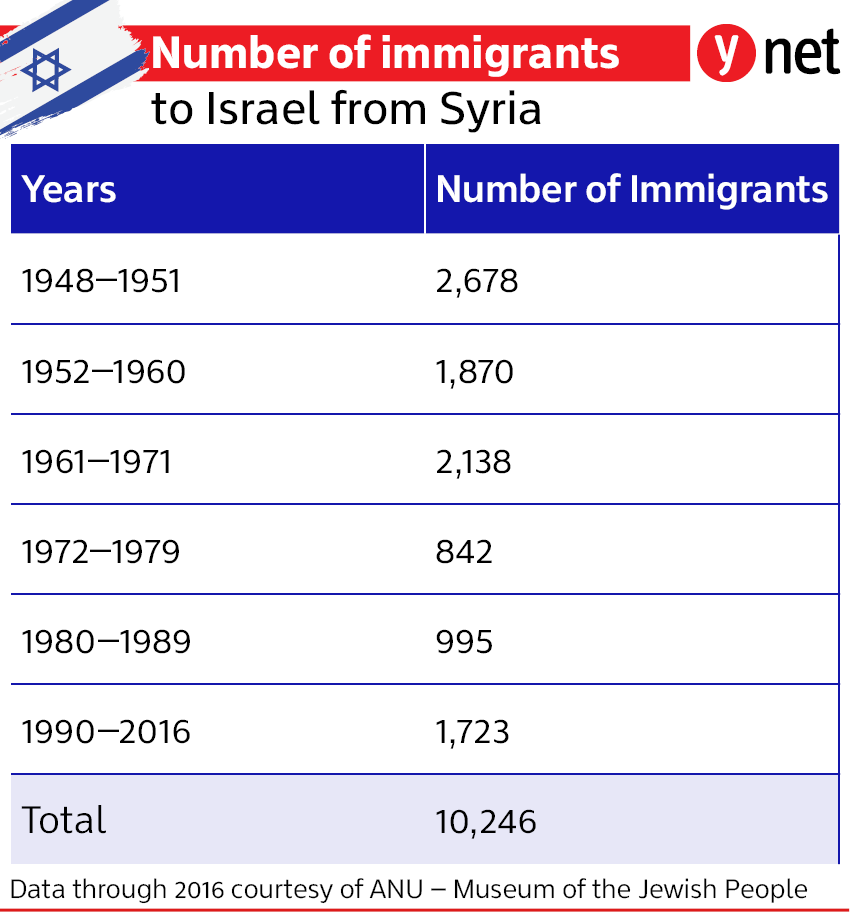

Following the creation of Israel, a wave of Syrian Jewish emigration drastically reduced the community, with only a few thousand remaining in Syria. “Most of the emigration was via Lebanon," says Zisser. "From there, some carried on to Israel, others to locations in Mexico, Argentina, and the U.S. where there were already Syrian Jewish communities. By the end of this wave of emigration, there were around 5,000 Jews left in Syria living under increasingly strict government control."

What was it like for Jews under Hafez Assad?

"During Assad’s rule, surveillance was stepped up. There was a security organization keeping an eye on the Jews, monitoring and restricting their movements and occupations. Although there were no serious riots or any kind of persecution, restrictions made things very difficult. Arranging marriages for the community’s Jewish women, who invariably found themselves unable to leave the country, or facing an assortment of hostility. Some community members managed to leave gradually, but most found they had to wait until 1992 when Assad permitted larger-scale emigration. After that, only a few hundred Jews were left in Syria – either since they chose to stay or couldn’t leave for various reasons. Some of those who left immigrated to Israel. Others joined relatives overseas."

Syrian Jews were dispersed to various parts of the world. Some, obviously, made their way to Israel, while sizeable communities also formed in Mexico City, Argentina, the U.S. and Panama. Businessman and philanthropist Isaac Assa, whose father, Benjamin Assa, was a leader in Mexico’s Syrian Jewish community, tells us that he emigrated with his family as a child to Mexico where they joined the existing Syrian Jewish community, founded 1900-1930 amid deteriorating conditions in Syria.

Why Mexico?

"They didn’t really choose Mexico. My family immigrated in the second wave in 1948 and ended up in Mexico as a result of various circumstances: Originally, they wanted to go to the U.S., but were denied entry due to concerns regarding contagious diseases. They eventually found their way to Veracruz, Mexico, and from there moved to Mexico City. While many dreamed of going to the US, Mexico was a developed country in terms of industry and there were lots of opportunities for new immigrants. The fact that there was already a Jewish community there was also a major advantage."

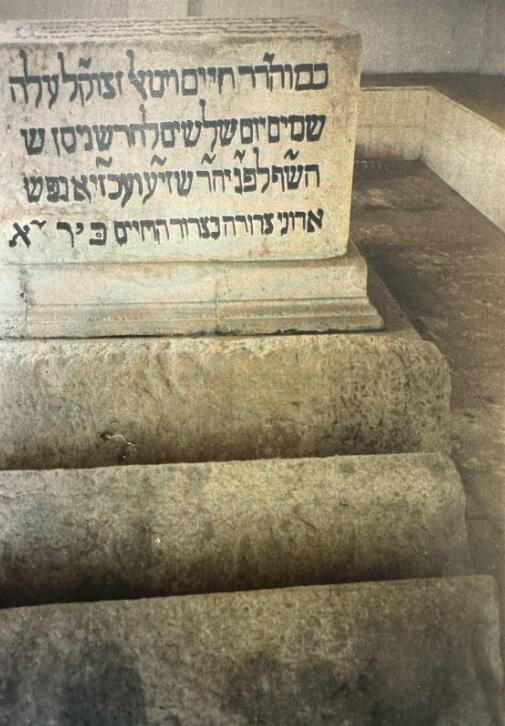

Assa says that the decision to emigrate arose from increasing tensions with Syrian Muslims after the establishment of the State of Israel and a series of violent incidents, including a grenade attack inside Damascus’s Al-Manseh synagogue in 1949.

That Friday night attack killed 12 Jews and wounded 60. "My father, who was only 15 at the time, was in the synagogue that night. His best friend died in his arms. After that incident, he and other young men realized they had to leave. With other Jewish young men, he crossed into Israel via the Golan Heights at night. Most of them remained in Israel and joined the IDF. My father served in the army and stayed in Israel until 1957, when he joined his family in Mexico, where he got married and stayed.

What’s the Syrian Jewish community in Mexico like today?

"The community consists not only of Syrian Jews but also Jews from other places, including the Balkans and Ashkenazi Jews from Europe. The Syrian Jewish community is divided into two main groups: Jews from Damascus and those from Aleppo. The community is very organized, with a variety of institutions and schools teaching Hebrew and Zionist values. There’s healthy competition between the two groups, pushing us to strive for excellence. I’ve heard all the stories about the tensions between the Aleppo and Damascus Jews, but it’s not all tensions: I’m from Aleppo and my wife is from Damascus, and there are lots of couples like us. At the end of the day, we’re all Syrian Jews – even with these minor cultural differences. The community numbers about 30,000 and has over 40 synagogues. Most of the community is religious or traditional."

Where else can Syrian Jewish communities be found today?

Aside from Israel and Mexico, there are large communities in New York, Buenos Aires in Argentina, Brazil, and Panama. In some places, it’s difficult to know how many people belong to the Syrian community: In Israel, for example, the second generation has integrated with Jews from other countries. There are strong ties between the communities. I often visit Israel and stay in touch with Syrian Jews in the US and other countries. We share customs and traditions, and I always enjoy finding fellow community members in different parts of the world.

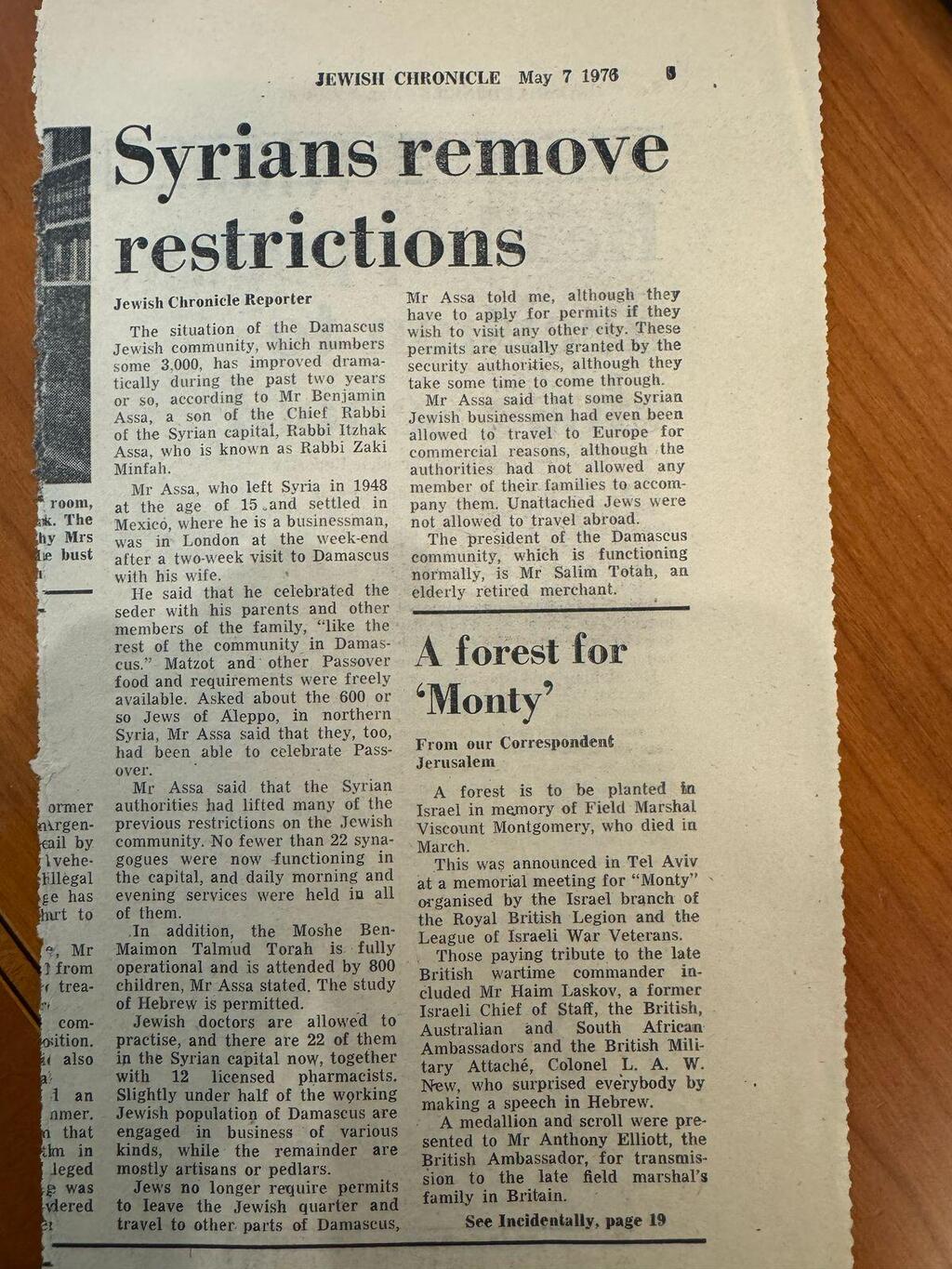

Assa recounts how he joined his father on a visit to Syria that his father managed to arrange in 1976: "My father was the first Syrian-born Jew to go back to a visit. He was very much looking forward to seeing his parents whom hadn’t seen for 26 years. He traveled on his Mexican passport and, to ensure being permitted entrance, gave an interview to the press, praising the Syrian regime and its treatment of Jews.

"What he said in the interview was obviously untrue. He had one goal, however, and the regime was glad to have positive coverage. This allowed him to enter and leave Syria without any issues. He later brought his parents to Mexico for a 'visit,' under the condition that they would return to Syria. He then forged death certificates for them, and sent them to Syria to explain why they never returned to Damascus."

What do you remember from the visit with your father to Syria in 1976?

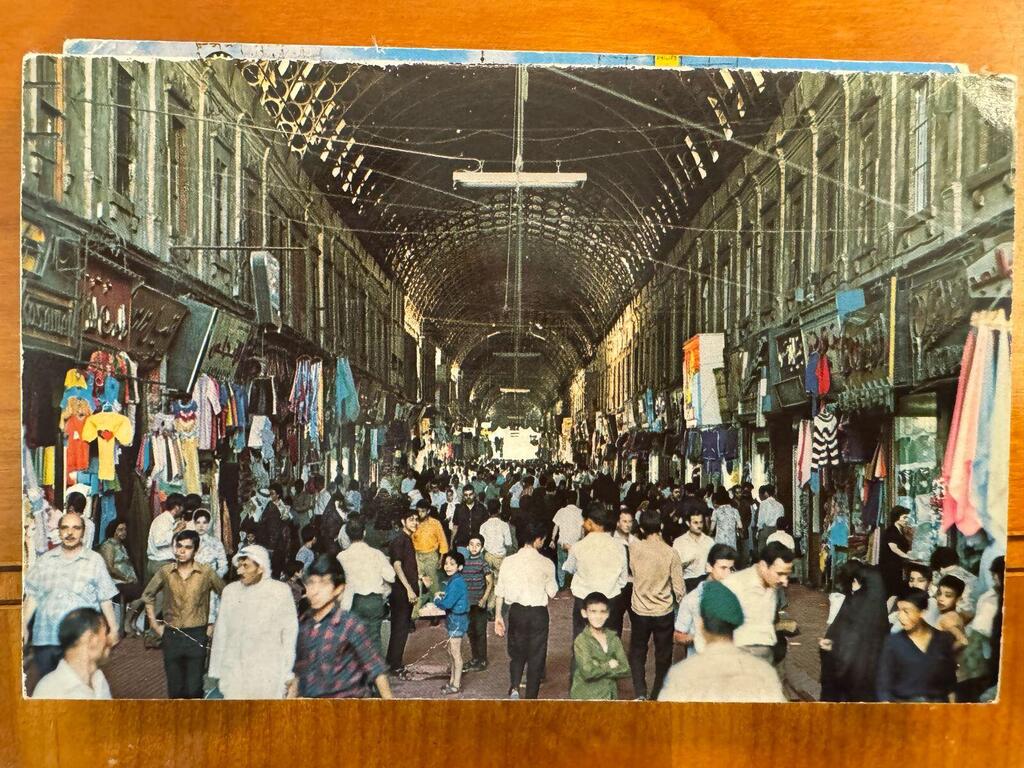

“I was very happy to meet relatives who’d stayed there and to see what was left of the Jewish community. Conditions, however, were poor, and I was sensing hostility from the locals: we were cursed by a shopkeeper while out shopping in the market. We couldn't respond as were the majority and were in charge. The whole area was old and neglected. There was no running water, and people worked low-grade jobs. You definitely couldn’t say their situation was good. But lots of people came to see us and talk to us while we were there. It was heartwarming to sit with them and hear the stories about our roots."

What are your thoughts about everything that’s happened in Syria in recent years and the new Ahmad al-Sharaa regime?

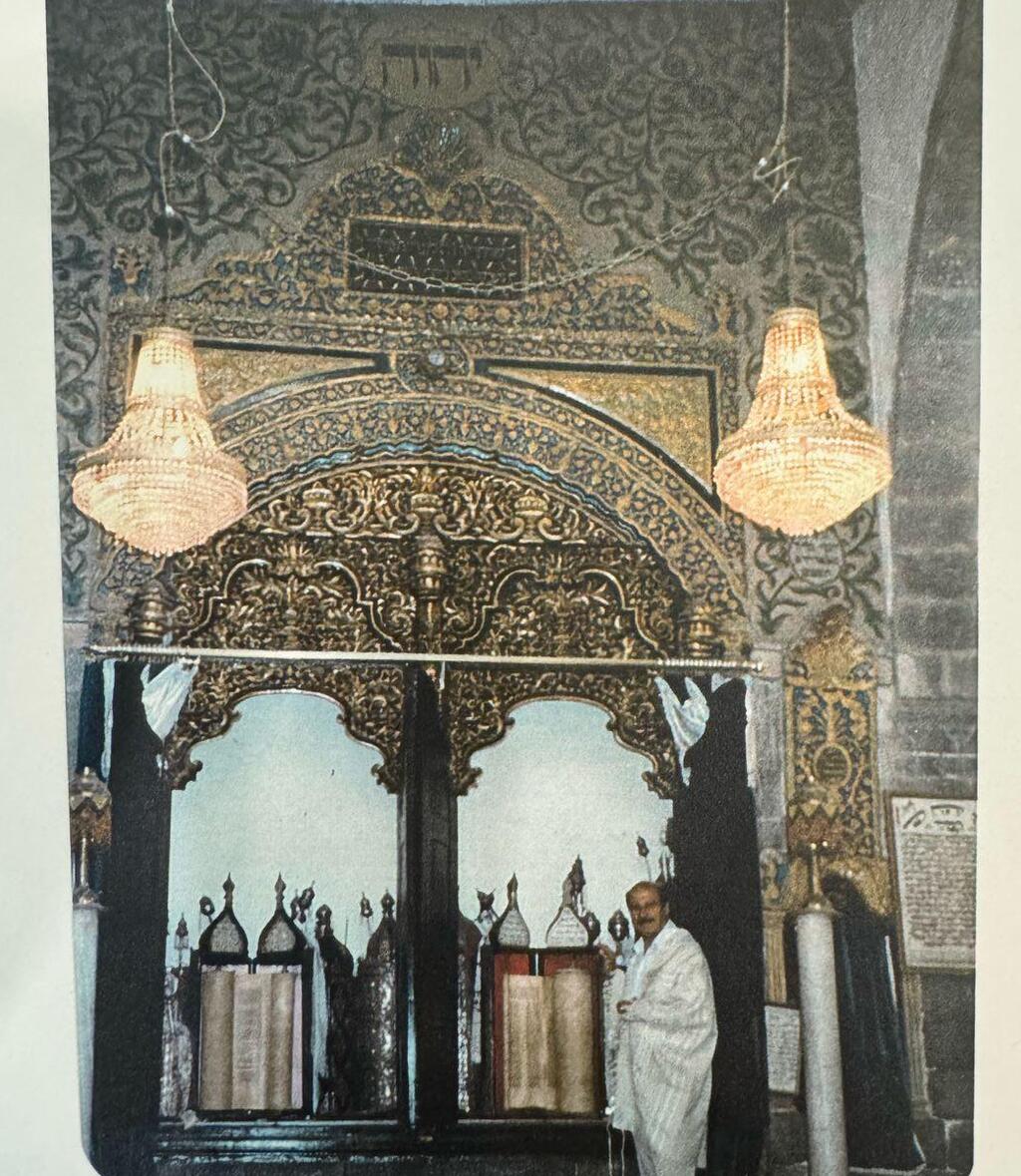

"I think what really matters is that we are Syrian Jews, and that's the main thing. The land, Damascus, Aleppo, are no longer important, at least not to me. What is special is our tradition, our values and community cohesion. Personally, I have no connection to, or special feelings toward, Syria. If anything, I’m angry. I remember everything they did to us there and the way we were treated. I love the community, our prayers, food and traditions. The place itself means nothing to me. That’s why all the talk about wanting to restore the Damascus synagogue or other community sites seems rather pointless to me. There’s no Jewish community there. Why restore a synagogue without a congregation? It’s just talk. That place is over for the Jews."

According to a recent report by Justice for Jews from Arab Countries (JJAC), only four Jews remain in Syria today, all in Damascus.

Some Syrian Jews, of course, emigrated to Israel and have, over the years, settled in various parts of the country, the most sizeable Syrian Jewish communities primarily in Holon and Bat Yam. There are also active synagogues adhering to Syrian customs in other parts of the country, including Jerusalem, Haifa and Tel Aviv.

As part of the Seeing the Voices project documenting testimonies of Jews from Arab countries, Nathan Hasson, born in 1932, describes the harsh conditions he faced during his childhood in Damascus: although there were several wealthy individuals within the community, poverty and deprivation were widespread. As the Zionist movement grew, so did the Jewish community’s connections with the Land of Israel. He left Syria in 1945 for the Land of Israel, settling in Kibbutz Ginegar. He later served as an immigration emissary in Algeria, worked for both the Shin Bet and the Mossad, and in various economic-related positions in Africa. He says that, while much of the community dispersed to different countries, he had always wanted to come to Israel: "I dreamed about the Land of Israel my whole life and never once considered going anywhere else."

He told Ynet, that he was active in the Organizacion de los Judios Damascenos (de Syria) and edited the expatriate community's magazine, “We put on events and have also set up a website where we post articles and testimonies about Jews from Damascus, carrying on the tradition. It was important for us to preserve the customs, unique foods and strong bonds within the community. We held activities and gatherings, published a magazine, and worked to connect the younger generation to their heritage. This is a very special community, and we want to ensure that it is remembered and continues to exist."

Solve the mystery: What’s the real relationship between the Jews of Damascus and Aleppo?

"In theory, we’re partners. In practice, we’re not. We wanted to set up a heritage center for Syrian Jews. We started planning it, but didn’t have enough resources. The Aleppines weren’t in, and the whole thing collapsed. The communities aren’t fundamentally different, but there are some distinctions, including religious differences, and not everyone always wants to collaborate."

How do you feel about today’s Syria?

"No one knows what’s going to happen. Today's Syria is ruled by one leader, with various groups who, in the not-so-distant past, were all terrorists. It's not clear what al-Sharaa wants or whether he wants to have relations with Israel. Today’s Damascus looks nothing at all like the one we left. Syria is made up of so many groups—Kurds, Druze, Alawites and many more. They’ve never really gotten along and it’s been damaging the country for years."