Last Sunday, Zahava received what may be the last WhatsApp message from a childhood friend in Shiraz. It was relayed through her friend’s sister. “In Persian, she wrote that the police had taken the cantors and rabbis in for questioning. They were suspected of collaborating with Israel. To this day, we don’t know if they’ve been released,” Zahava said from her home in Haifa, her voice tense with concern.

“She told us it’s best not to contact the Jews there right now—the situation is extremely fragile. We used to be in touch daily. There’s a very active WhatsApp group that keeps everyone updated, but since the war started, there’s been complete silence.

"The Jews are staying inside, too afraid to go out for fear it could cost them their lives. They’ve disconnected from the internet so that no messages or information can leak out. During times like these, we’re careful not to reach out, to avoid giving the regime any excuse to harm them,” Zahava explained.

“The Jews in Iran don’t have a problem with daily life. If they did, they’d have tried to immigrate to Israel. They’re educated, employed and respected by the Muslim majority. The issue is with the regime and its deep suspicion of anyone with ties to Israel. The government doesn’t hate Jews—it fears Zionists.”

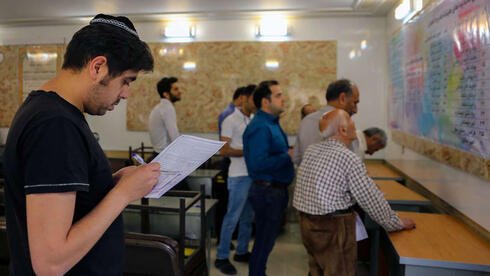

Noga, a New Yorker who left Shiraz following the 1979 Islamic Revolution, says the city’s Jewish community numbers around 7,000—mostly religious—and lives within a complex system of delicate balances with the Iranian regime.

“When there’s a conflict in Israel, the government forces the Jews to publicly declare that they’re against Zionism,” she explains. “It’s the regime’s way of separating Judaism from Zionism—showing that the Jews are loyal to Iran. And when Iranian leaders issue threats against ‘collaborators with the Zionists,’ the fear can be paralyzing.”

According to Noga, many Jews in Shiraz would love to speak out—but these days, every phone call carries risk. “If you call from Israel, they know. They just know.”

When was the last time you spoke to anyone there?

“On the first day of the war. It was a call like all the ones before—‘Hello, how are you?’ They answered, ‘We’re fine.’ We replied, ‘Okay, goodbye,’ and hung up. The next day, my cousin spoke briefly with his parents in Shiraz. They said they’d been hearing explosions, but didn’t say much more.

"Because of my ties to Israel, I personally avoid calling them. Most of the contact is through cousins who’ve never been to Israel. We’re certain that Iran’s intelligence services keep a kind of ‘blacklist’—they know exactly which Jews have ties to people connected to Israel, and who doesn’t.”

Reflecting on conversations in the days leading up to the war, she says: “The communication is very short, concise and far from revealing what’s actually going on. We talk about fashion, about family weddings—anything that avoids the real issues. And when we do touch on them, the language is always coded.

"The questions come from the world of weather—it’s how we understand if things are good or bad: Is it stormy or cold? Hot or is a storm coming? And the answer might be something like, ‘Right now things are okay, but we heard tomorrow there’ll be a flood,’ or, ‘An earthquake is expected.’ That’s how I gather information about how they’re really doing in sensitive times.”

Can you give an example?

“For instance, when the ayatollah spoke about ‘Zionist spies’ and made statements like, ‘We will catch the traitors, deal with their families and not let them continue to live,'” Noga says.

“Still, in normal times—so long as Jews don’t stand out, keep a low profile and live quietly—life there is actually quite good. Business is good, the food is great, families are together and they enjoy a fair amount of freedom. But if you do anything that draws attention, even the wealthy, influential Jews are not protected from the regime.”

Noga mentions influential figures within the Jewish community, prompting a question about the recent interrogations of religious leaders.

“Shiraz will always be my city, but Iran is no longer my country. Before the revolution, they used to call it ‘the Paris of the Middle East.’ Now, despite all their advanced missiles, the mullah regime has dragged it back a hundred years."

“The regime will stop at nothing to instill deep fear in the community,” she says. “They’ll make an example of anyone they suspect of collaborating with Israel. If it’s true that rabbis or cantors were detained, it’s a very troubling situation, and urgent action is needed to secure their release.”

Noga also opens up about the emotional toll. “Sometimes my husband and I watch the news from Iran and we just cry. You see the heavy presence of the Sapo—the special police that hunt down citizens who speak out against the ayatollah. You see the bombings, the collapsed buildings, the destruction in the streets. The death toll and number of wounded rises daily—and we can’t even get updates about the condition of our loved ones over there.

"At the same time, all of us—even Iranian Jews themselves—feel that finally, Israel is doing what maybe it should have done 30 years ago. So we’re watching both fronts with anxiety and heartbreak but what is happening in Israel is more painful. My son, my brother and my cousins live in Israel. I hear how they run in fear with their small children to bomb shelters in the middle of the night. And it hurts.”

“Shiraz will always be my city, but Iran is no longer my country,” says Noga. “Before the revolution, they used to call it ‘the Paris of the Middle East.’ Now, despite all their advanced missiles, the mullah regime has dragged it back a hundred years. That’s why we hope this is their end. Let them go to hell so that everyone can finally breathe. In the meantime, we’re all keeping a low profile and waiting.”

Noga emphasizes, “People need to understand: Persians are not a stupid people. The ones pulling the strings—the government officials, the heads of the media—they’re educated, with degrees from top universities in the U.S. and Europe. They speak multiple languages.

“In the past, Persian immigrants who came to Israel for a better life often arrived with nothing—no money, no education. Today, I look around and see engineers, doctors and influential figures in key positions, many of them of Persian descent—mostly Jews, but not only. Outside of Iran, they’ve found the opportunities that were denied to them back home.

“Even today, it’s extremely difficult for Jews in Iran to get into university. Priority goes first to the children of mullahs—especially those who lost someone in war. Then to Muslims. Only at the very end, maybe, a Jew—and only if he’s a real genius. To this day, Jews can’t work for most companies—especially government ones, but even many private firms—unless they have a Muslim partner. That’s the reality. So no matter what Jews there are forced to show outwardly, from what I know of them, they all agree: these mullahs need to go to hell so Iran can return to the days of the Shah, to the beloved country it once was.”

6 View gallery

Iran's Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei

(Photo: Office of the Iranian Supreme Leader/WANA (West Asia News Agency)/Handout via REUTERS)

She laughs wryly: “There’s even a joke going around among us—‘Passover 2026, we’re all celebrating in Shiraz.’ That’s how confident we are that Israel will finish them off once and for all, and finally free our brothers in Iran.”

Noga takes a deep breath, then adds, “God willing. In the meantime, we’re dreaming of the day after—the day we’ll all sit together in living rooms, whether in Israel, America or Iran, and tell our grandchildren and great-grandchildren about the historic miracle that Israel made happen. How, in just a few days—God willing—the Israelis gave us back our country. How they freed them from the mullahs. Look, we’re in the middle of a war. People still don’t grasp what an enormous favor the State of Israel is doing for the whole world by eliminating the head of the snake. It’s the end of a dark era.”

Nearly three decades ago, Lydia left her parents’ home in Tehran. Speaking now from her home in Holon, she shares details of an unusual phone call she had last Saturday with her brother and his wife—unusual, she says, because most conversations are typically limited to “How are you?” and “Is everything okay?” without ever knowing what they’re truly going through.

Her brother, who lives in northern Tehran, told her they were warned that anyone in the Jewish community with ties to Israel would be arrested and sent to prison. His wife added, “We had nowhere to go, so we went to an aunt’s house in the western part of the city. It’s safer there. It’s a big house where all the children and grandchildren are staying together.”

Her brother also told her that from his balcony, he saw Israeli planes bombing targets nearby. “We waved to the pilots and loved seeing the Israeli army in action,” he said. “Redemption has arrived. We thank the Creator.” He said clearly: “Now that Israel has come to help us, there will finally be peace in Iran.”

According to Lydia, even before the October 7 attack, some of her relatives had tried to flee to America. It was during the COVID-19 pandemic—they sold off their belongings and packed one suitcase each, “as if they were going on vacation.” But things quickly unraveled. “Four members of the family were killed. When I spoke to them, they sounded fine. Family members who visited said they just had a mild flu—and the next day they were gone.”

“Now everyone there is living in fear, not understanding how all of this suddenly fell upon them. The Iran-Iraq War was 40 years ago—most of them don’t even know what air raid sirens sound like. They’re living under existential chaos. And yet, all of that doesn’t scare them as much as the regime itself does. I’m talking about the leadership that, over the years, slaughtered, murdered, raped, cut women’s lips for wearing lipstick, issued massive fines for nothing, and turned people’s lives into hell.”

Speaking of redemption, Lydia adds with a half-smile: “All my girlfriends from Iran adore Bibi [Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu]. They see him as the messiah who will save them. They say, ‘Bibi, come be our prime minister. We love you.’”

For now, under the guidance of Iranian exiles abroad—like the son of the former Shah, who lives in the U.S.—Iranian Jews are staying silent. They are not taking part in protests. They’re shut in their homes, not even going to work—at least not until Israel finishes what it started and delivers them.”

Ben, from Texas, whose parents emigrated from Shiraz and Tehran as young adults, also speaks about the caution and coded language that now define conversations with relatives in Iran.

“For us, it’s more of an open-ended question—and from the tone of voice, we can usually sense what they’re really going through,” he says. “These conversations are extremely careful and measured, because we understand how dangerous every word can be. In this wartime reality, we prefer to wait patiently for the day after—even though everyone here is on edge, biting their nails, and deeply worried about our families’ fate.”

“The situation is complex,” Ben continues. “On the one hand, we’re all happy that Israel is hitting Iran with a ‘hammer blow.’ On the other hand, there’s still a Jewish community there that’s caught in the middle—and we don’t yet know how this war will end, or what level of destruction and loss the community will be forced to endure.”

"It was clear to me that asking how they were really feeling was a risky question—and we didn’t expect a truthful answer."

“In the meantime, we’re glued to news reports coming out of Iran and comb through every bit of information on social media. We’ve even seen videos of Muslims dancing in the streets—literally—celebrating and handing out sweets, blessing the Israeli army for coming to save them. But the Jews? They don’t dare do that. You won’t see them dancing, or shouting ‘Death to Khamenei.’”

Recalling the last conversation his mother Patti had with a close relative in Tehran, Ben says: “It was on Friday, the day the war broke out. My mom asked if everything was okay, and they gave the expected, terse response: ‘Thank you for asking. We’re on our way to synagogue. Don’t worry—we’ll talk sometime.’ Since then, we haven’t been able to reach them. It was clear to me that asking how they were really feeling was a risky question—and we didn’t expect a truthful answer. Still, the worry and fear for their safety is enormous.”

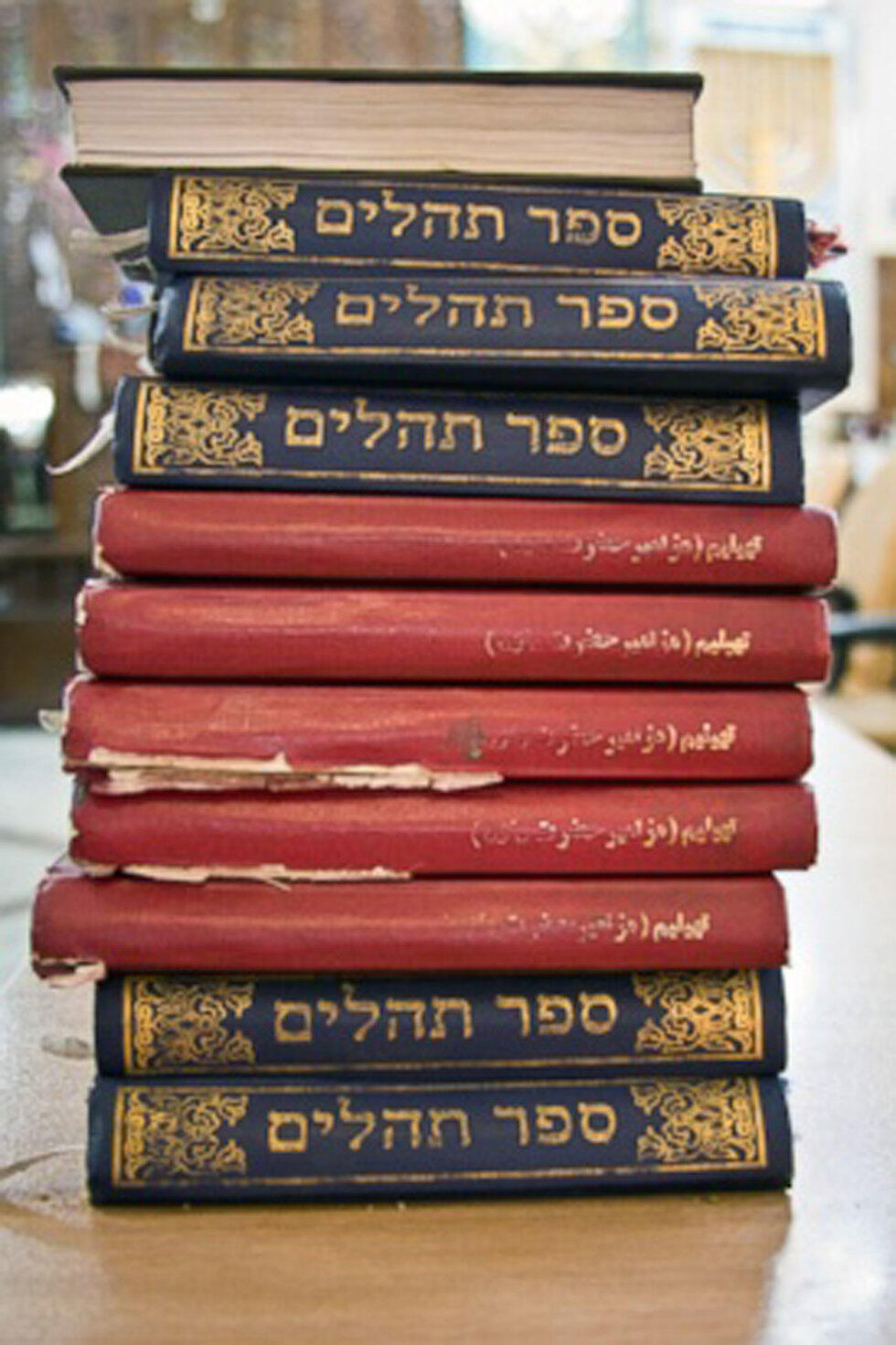

Ben speaks at length about Iran’s anti-Zionist Jewish rabbis and the controversial statements they’ve made—statements that have drawn sharp criticism around the world. Among them: “Zionists do not represent Judaism, only a political idea,” a remark by Rabbi Yehuda Gerami, the chief rabbi of Iran’s Jewish community. Another, more incendiary, came from Dr. Younes Hamami, a leading figure in Tehran’s Jewish community, who equated Zionism with a murderous terrorist organization, claiming “they commit war crimes and kill innocents in Gaza and Lebanon,” and “Zionism is like ISIS which commits violence in the name of Islam.”

Ben admits these words trouble him deeply. “When these rabbis visited our conferences and met with Jewish communities abroad, many confronted them with tough questions. But they didn’t really say what they believed. As angry as people were, everyone understands—they live in a reality where saying anything else could cost them their lives. I believe that once the regime falls, Jewish organizations in Iran will work to get the Jews out. Then you’ll start to hear different voices, different truths—spoken openly, without fear.”

When I share with Ben a Persian-language message reporting that Jewish religious leaders in Shiraz have been taken in for questioning, he responds calmly: “I hadn’t heard that, but I’m not surprised.” His mother, Patti, visibly concerned about the news, says firmly, “It’s entirely possible. And if they haven’t been released yet, I really hope they will be soon.”

Ben explains: “You have to think like the Iranian government. When they take the cantor or the rabbi, it sends a message. The community becomes frightened—and cooperates with whatever the regime wants. The government is rattled because they’re getting hit hard by Israel—and thank God for that. Now, they’re lashing out, targeting anyone they think is helping Israel or even just sympathetic. It’s not new—Jews have always been the first to be attacked, in every place they’ve lived. It happened in Arab countries, and it’s happening now in Iran—despite all the so-called respect shown to the Jewish community.”

“There’s also a tendency to underestimate the Iranian people—and that’s a mistake. Iranians are very savvy, very current. They use advanced technology from China. They’re not like the Arabs,” Ben says.

“Still, today, I’m proud to be a Jew. I was born and raised in the U.S., but Israel will always be my home. And now, with great hope, we pray for the change that must come—the day when Iranian Jews can finally speak the truth out loud, without fear, as free citizens wherever they choose to live.” He ends with a smile: “Next year in free Iran."