The Holocaust is ever-present in my life, and I make room for it; I never escape, ignore, or suppress it. Not a day goes by without a thought that relates, directly or indirectly, to the Shoah. Time and again, I am moved by its presence in my life, awed by its impact, and give myself over to it.

The German language will forever stir a sense of distress and unease in me. Although it was decades ago, it still echoes the shouts of “Juden, Raus”, that expelled my father and his family from their home in Bendin (Będzin, Poland).

For 47 consecutive years, I’ve attended the Frankfurt Book Fair, wandering between the booths, meeting people, all while deep inside I could not wait for the official part to end, so I could step away and stand at the same train station from which German Jews were deported to the death camps, and bow my head.

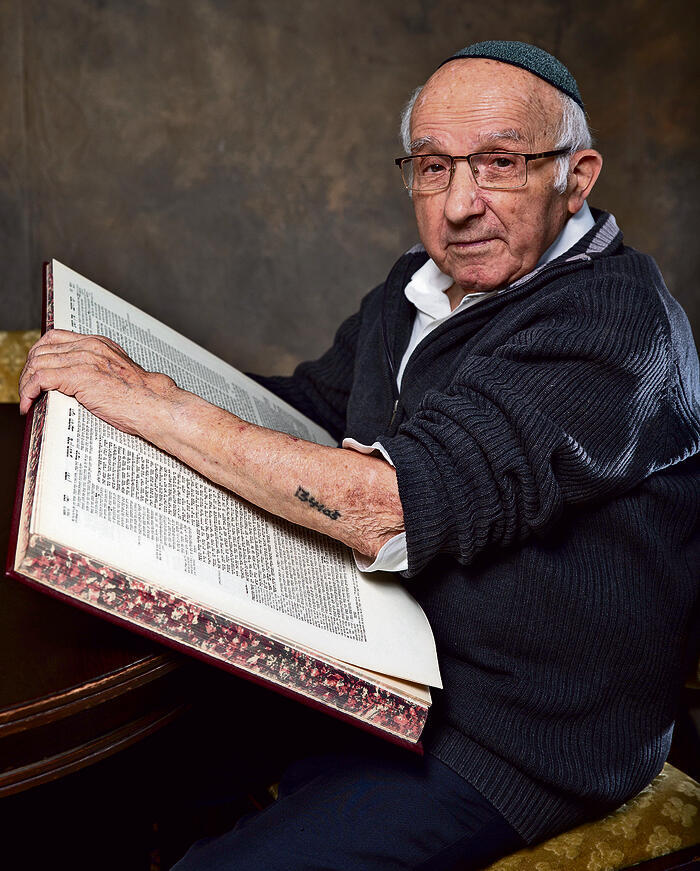

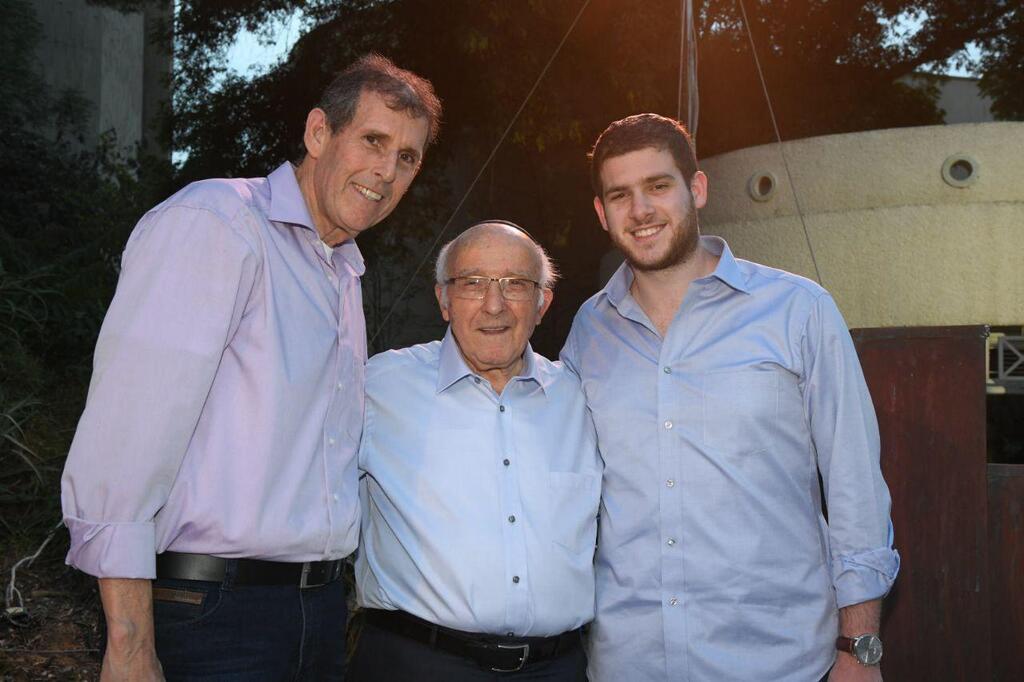

My father carried the inferno he had experienced until his final breath, and I carry his memory with me every day. In 2012, I created a personal ID tag – a silver dog tag engraved with the phrase “Every person has a number,” followed by three names and numbers: 134105 Zvi (Hershel) Eichenwald, 2230123 Maj. (res.) Dov Eichenwald, 5283310 Capt. (res.) Ofir Eichenwald. The first is the number which the Nazis tattooed on my father's left arm; the other two are the military ID numbers of my son and me when we joined the IDF.

7 View gallery

The silver dog tag includes numbers of the tattoo on Zvi Eichenwald's arm and IDF personal ID of Dovi and Ofir

(Photo: private album)

That dog tag represents the triumph of good over evil, the Holocaust and revival – the essence that guided my father and now guides his sons, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. My father often said he learned, in body and soul, what the Holocaust meant, and what revival meant. I learned it too, through him.

The Shoah (Holocaust) and the revival are the genetic code of our family, and that dog tag is a key part of who I am. I never take it off; I can't take it off, because it would be like peeling off my own skin. The letters engraved on that piece of metal remind me of the profound meaning of generational continuity, both familial and national, and my commitment to it.

The Holocaust takes up a major place in my life. It shaped me, influenced my choices, consciously or unconsciously, defined how I navigated my life, and molded who I was as a son, who I am as a father to my seven children, a grandfather to my 24 grandchildren, a friend, and a manager.

I consider the home I grew up in a sheer miracle. Given the anguish my parents had endured – my mother was born in Jerusalem and survived the harsh siege of the Old City – it would have been natural for bitterness to take root. But as the poet Yehuda Amichai wrote, “My mother baked the whole world for me in sweet cakes”, that’s how our parents raised their three children; they wrapped us in boundless love and appreciation.

My earliest childhood memory is of our small family – parents and three children – gathered around the Shabbat table in our Bnei Brak apartment. My mother was serving food when suddenly my father said he wanted to share something.

In his soft, gentle voice, he reminisced about a time long ago: “When I was in Fünfteichen, a labor camp I was sent to from Auschwitz, I worked in greasing machines. I had a severe eye infection that blurred my eyesight. One night, I went to the clinic, and luckily, the doctor demanded that I be taken to the hospital. There, luckily again, a Jewish doctor gave me eye drops, and thus I regained my sight.

“I spent a week in that hospital, and there I witnessed the 'valley of death'. People died from starvation, malaria, infections, and dysentery. Bodies piled up daily. I would approach the dying people when I could.

"To this day, I hear their final whispers: ‘Remember that my name is… If you meet my family, tell them you saw me here. I'm going to die. Please, don't forget my name.’ They mentioned their first and last names, their towns, pleading me not to abandon them, asking me to repeat their names. They knew death was near, and in those final hours, they clung to the memory of their names. I wept without tears. From the lump in my throat, I promised them that if I lived, I would remember."

I was nine years old that Friday night, watching my father’s gentle face contort with pain as he was pulled back in time into that hospital. The sounds echoed again in his ears, and the memory overtook him.

It was the first time I heard him recount even one episode from the countless horrors he has experienced, a story that never let me go. I remember repeating the word Fünfteichen to myself, so I wouldn’t forget that such a horrible place existed on Earth. I presume that in that Shabbat night in Bnei Brak, the mission that my father had accepted – to be a messenger for those miserable people going to their deaths – was passed on to me: to remember their names.

The stories of the Holocaust were never silenced in our home; my father always shared, and we always listened. I remember myself devouring every detail, trying to imagine what he had endured, often failing to do so.

He was only 13 when he entered the kingdom of death. His parents were taken from their home to Auschwitz, and he was sent, together with his eight siblings, to the ghetto which was established on the city’s outskirts. Eventually, they too were sent to the Auschwitz ramp.

As they stepped off the train, the German soldiers conducted a selection (deciding who was qualified for labor and who was to be killed immediately). Sensing the stakes, when German officers demanded his age, my father lied and said he was 18. He was sent to labor, while his younger siblings were sent to the gas chambers. He would forever carry the cry of his little brother Yossel, who begged to stay close, a plea he ignored to protect his lie.

My father survived five years of Nazi abuse – the ghetto, selections, labor camps, Auschwitz, and the death march. In 1949, he immigrated to Israel and joined the IDF. He was a lone soldier, alone in the world.

The father I came to know was shaped by those WWII war years. Together with my mother, he built a home. My mother, in her quiet and simplicity, learned to contain the chaos that inhabited her husband’s soul.

My father chose not to be consumed by darkness, but rather allow the light to shine through, seeing the good in people rather than the monstrous. Until his passing at the age of 96, he never forgot the stranger who helped him during the Death March, keeping him from giving up.

My father chose optimism, which helped him deal with the inconceivable. I inherited these traits and made them part of my own code of living. I am deeply optimistic, and I believe optimism is not something you can preach; you're born with it. Our home was steeped in it.

Amid the broken life my father carried within him, there was a fullness of faith in humanity, a drive to give and to act. My older brother Haim was a tank commander during the Yom Kippur War. It took me years to fully grasp the meaning of the term “shell shock” (PTSD), which is what my brother had lived through.

Years later, his son Elad suffered severe burns all over his body during a Holocaust Remembrance Day ceremony at his school. But my father never saw despair as an option. He summoned all his strength, stood tall, and became the rock we all leaned on.

My father was our most significant anchor in the hardest of times, never whining, never self-pitying. We never heard him asking, “Why me?”, although we knew the pain and anguish within him, which never vanished.

It was thanks to him that Haim, my brother, learned to live with his PTSD. It was thanks to him that I learned to move forward without bearing the 'disabled parking badge'. And thanks to him, Elad, his grandson, drew the strength to study medicine and become a beloved pediatrician.

The reckoning he had with the world that had wronged him, his family, and his people, along with his doubts and the difficult questions he had for G-d, my father kept to himself. When I asked him how come he was the only one from his large family who survived, he replied without hesitation, “In heaven, they must have decided I should live.”

The belief that 'G-d's ways are hidden', and 'you should not seek things concealed from you', gave him an answer he could live with in peace, without bitterness or misery.

On every milestone birthday, my father would say he was getting closer to the day when he would finally receive answers from G-d. He understood Holocaust survivors who turned away from religion. He chose faith. He studied and taught Mishnah daily, learned the Daf Yomi (daily page of Talmud), attended Minyan prayers, and continued to ask hard questions, but I never heard him rage or rebel. In all our conversations, he would always begin and end with the same message: Whether religious or not, what matters most is being a moral human being.

I didn’t live through the Holocaust, but I’ve lived its echoes. Like my father, I too experienced life triumphing over death.

In June 1982, the first Lebanon War broke out. On the fourth day, I was called up for reserve duty and deployed to Lebanon. Gunfire, grenades, and roadside bombs were part of our routine.

As a military police officer, I gathered my soldiers and closed our briefing with one request: “I'm just asking for one thing – that we all, with no exception, return home safe.” It did not happen. On November 11, 1982, I sat down for breakfast with four team members in the building where we were based, located on the road between Tyre and Sidon. Suddenly, a massive explosion was heard, and the building collapsed. The next thing I remember was that I was trapped in complete darkness, unable to move.

The terrifying moments seemed to last forever. Buried under rubble, I was certain I would die. My thoughts raced to my two daughters – Roni, a baby, and Lior, just two years old, who would grow up without a father. My father's orphanhood flashed through my mind. I was covered in stones, but a box of ice that had somehow fallen on me created a narrow gap through which I could breathe, saving me from suffocation or being crushed by beams and concrete. The groans of my soldiers gradually faded, until a horrific silence remained. I thought of Itzik Klein, a soldier in my unit, who was the son of Holocaust survivors like me. Before we entered Lebanon, he had told me he was scared, and I admitted I was too. Itzik was one of 76 killed. I thought about his father, the holocaust survivor, and mine.

When I was rescued after long hours, I strongly felt I was reborn. As I was lifted onto a stretcher and placed in a helicopter, the only words in my mind were: “I was born again. My life has been given to me as a gift.”

7 View gallery

A wounded rescued from the rubble of a building in Tyre

(Photo: Miki Shovitch, G.P.O)

I went through a year filled with painful recovery – hospitalization, intense and complex medical care – and one conversation that changed my life. My father, who would visit me daily, told me, just before I was discharged from the hospital: “Dovi, I suggest you move on with your life and focus on looking only forward.”

That sentence still echoes in me. It became my inner motto and my guiding light. Since then, every morning I remind myself that this could be my last day on earth. I must do what I want with no delays and no compromises, because who knows when the next building will fall on me, or when another twisted mind will try to erase me, as happened to the Eichenwald family of Będzin (Bendin).

Like my father, I was often asked how I was the only one who survived the Tyre disaster. Maybe it's another chapter of Holocaust and revival, the thread that runs through our family. Maybe it was luck. My usual answer is that I don’t know. To myself, I say that I survived by chance. I was randomly given a second life, and this is not a tale of heroism. Like my father, I decided not to live in death’s shadow. Unlike him, I buried it all, but I never forgot.

In 1984, I initiated our first trip to Poland. I learned that a delegation of historians from Bar-Ilan University was about to travel there, and I asked to join with my parents. I wanted to return with my father to his birthplace, to hear him recount his childhood and youth on the soil where it happened. And so, we went, my father, my mother, and I, to a Communist country still closed to the West.

On the first evening, when members of the delegation asked him to share his wartime story, he tried to keep his emotions at bay, stood before them, and began to speak. After ten minutes, he collapsed in tears and couldn’t go on. It was the first time I had ever seen my father in such a situation; it was the first time I felt the full force of the trauma. And it only deepened my admiration for his choice to cling to life despite everything.

When we returned to Israel, my mother confided her greatest fear, that my father wouldn’t survive that night in Poland. All she had wished for was to return to Israel.

That first trip to Poland marked the first time I recognized the Holocaust's imprint on me. It's what draws me back, again and again, to Poland, whose soil is saturated with Jewish blood. Images of the murdered and the piles of bodies surface in my mind in unexpected moments and contexts, just like the question I would repeatedly ask my father on our joint trips: 'How did you survive that horrible place?' And he would always give me the same answer: “I hope you never need to find out just how much strength lies inside each of us.” I hold on to that strength in my darkest hours.

7 View gallery

Zvi (Hershel) Eichenwald lights a torch on official Holocaust Remembrance Day ceremony

(Photo: Yair Sagi)

My father shared many stories from his past, each leaving its mark on me. But the story with the most influential impact on me was the one he told me during our visit to his hometown of Będzin, Poland (Bendin).

While we were walking, he suddenly stopped and started recalling: “After the war ended, I returned to Bendin, searching for anyone from my family, but I found no one. Nothing. Then, a stranger approached me and asked, ‘Are you Eichenwald?’ I said yes. He replied, ‘I knew your parents'.” My father paused to steady himself and explained: “I knew then that everyone was dead. But hearing someone mention the Eichenwalds, someone who had literally seen my father and mother, was a moment of pure happiness. I turned to the man and said, ‘There is an Eichenwald in this world'."

When my father finished that sentence, I knew my life was about to change. Those three words lit my path. At a time when many around me Hebraized their surnames to sound more Israeli, I never considered such an option. I am Eichenwald, and my calling is to preserve the memory of the oak (Eichen) forest (wald).

Since then, my subconscious has been leading me, insisting that no one could ever cut down that forest. No one will erase Eichenwald. I promised my father there would always be an Eichenwald in the world. And I took on the role of chronicler. Some say that my documenting turned into an obsession.

I document my children at every gathering, upload their photos to Facebook, Instagram, TikTok; I never forget that my father didn’t have even a single photo of his family. This was a family without faces, preserved only in the memoirs of Herschel-Zvi, the lone survivor. I am committed to making sure it never happens again.

I admit, I carry a deep scar, but there’s logic to it. Books and photo albums can be burned, but digital art cannot. No deranged dictator can erase our existence in this world. No one will ever again threaten an Eichenwald. There is and always will be an Eichenwald in this world.

The void left by the murder of six million people drives my need, as a publisher, to fill it with testimonies and stories. That void was planted in me as a child. My father spoke of his orphanhood, his solitude in the camps, the daily selections, the people who vanished in moments. I remember listening with much attention.

My father recalled with deep sorrow the Polish and Russian prisoners at Auschwitz who received packages from home. He and the other Jews who were with him received nothing, because they had no country to care for them.

From an early age, we were told about the importance of the State of Israel and the IDF, hearing the sentence often repeated: “If we had had an army back then, history would have been different.” I absorbed that message as a child.

My father screamed his nightmares in his sleep. I remember the screams, my mother waking him, and his brief silence before the next scream. My mother, in her wisdom, knew how to contain his past; to her three children she explained that he was dreaming about the Holocaust, and made no fuss of it.

As a child, I took the screams as part of life. We lived in a neighborhood filled with Holocaust survivors. A woman living next door lost her children. Across the street, there was a man who would roam the streets, muttering in Yiddish, and we called him 'the crazy one'.

In the last two years, my wife Tali has been waking me in the middle of the night. “Dovi, you’re shouting,” she says, and I wake up in panic. “Sorry,” I would mumble. “I dreamt I was suffocating under rubble, surrounded by bodies.” I turn over, think of my father, and try to sleep.

Nearly 43 years have passed since the Tyre disaster. I was trapped under the collapsing building for just nine hours, but I still relive that nightmare several times a week. My father endured six years of hell, then orphanhood, everlasting longing, and decades of sleepless nights accompanied by screaming. Now the screams connect us.

In 2004, we asked my father to write the story of the boy he had been, and his journey through the depths of the inferno. He was in his early 70s. I gently urged him, reminding him that memory fades, and asked him to write it for the family. He agreed on the condition that he only recount what he had personally experienced or heard, and there would be no added details by historical research, no reconstructions.

The writing released something in him. Sometimes I think that the horror of what he witnessed was the reason he chose to focus on the good people he met, those who helped him without expecting anything in return. In the total evil and darkness, he insisted on focusing on the shred of light.

Over the years, I learned to interpret his silences, the subtle shifts in his mood reflected by his body language, the deep sorrow that permanently inhabited his soul, and the way he still made space for boundless optimism.

He named his children after his dead beloved family members. His grandchildren are named after his nine siblings. I never required my children or grandchildren to live as walking memorials. Each absorbed the family’s story in their own way. But none of us doubts: the Jewish people have no other land.

Although I am a product of the Holocaust, I do not see myself as an anxious person. I try not to give room to dark scenarios. Like my father, I choose to see the light and the good, to be optimistic even when it's hard.