We use units of measurement constantly, often without noticing, in every aspect of our lives. We measure vehicle speed in miles or kilometers per hour and the temperature outside in degrees Fahrenheit or Celsius. When baking, we measure ingredients in ounces, cups, grams, or milliliters.

Electricity is measured in volts or amperes, while the efficiency of electrical appliances is expressed in watt-hours. These are just a few of the many measurement units we rely on daily.

Measurement units such as the meter, foot, kilogram, and pound were created to provide a common language. As science became international, the International System of Units (SI) established a standardized framework, ensuring that measurements are consistent worldwide. But how is a meter—or a foot—defined? And who decides which units of measurement exist?

In the past, there was no globally standardized system of measurement. Instead, different cultures and communities used their own units of measurement. For example, the Bible mentions the cubit, a unit of length based on the distance from the elbow to the fingertips. Since arm lengths vary from person to person, the cubit was not a fixed measurement, but it provided a common reference that people could rely on for practical purposes.

During the 18th century, as part of the Age of Enlightenment, efforts began to establish standardized measurement systems. France introduced units such as the meter and the kilogram, promoting their adoption in other countries to enable accurate trade and scientific collaboration. In 1875, representatives from 17 nations signed an international treaty agreeing on the meter and the kilogram as global standards for units of measurement, leading to the establishment of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM). Its role was to oversee and coordinate the definition and maintenance of internationally accepted measurement units—a responsibility it continues to uphold today.

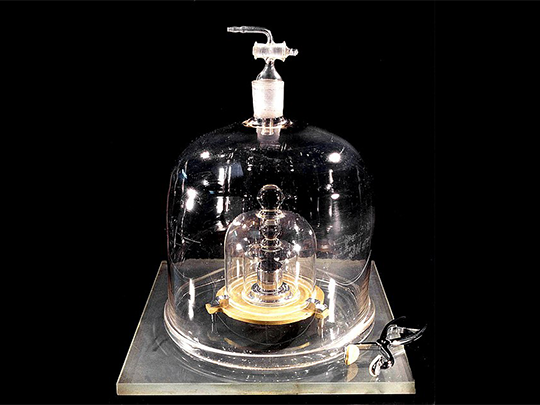

4 View gallery

The standard kilogram weight, housed within protective glass enclosures

(Photo: BIPM)

How were measurement units originally defined? The method was straightforward: selecting a value accessible to everyone and using it as a reference. For example, the meter was initially defined as one ten-millionth of the distance from the North Pole to the equator, while the gram was set as the mass of a cube of water with sides measuring one centimeter. While these definitions were universally accepted, they posed challenges, as they required highly precise measurements of distances and masses, which were difficult to obtain at the time. Meanwhile, other systems, such as the imperial system, defined units based on body parts (e.g., the foot) or familiar objects (e.g., the grain for weight).

When the BIPM was founded, the approach to measurement shifted to relying on physical reference objects. A metal rod of a precise length was designated as the standard meter, with identical copies distributed worldwide to ensure consistency. This allowed measurements to be standardized based on the official meter. Similarly, a carefully cast weight was established as the official kilogram. The second was also defined using a widely available natural reference—1/86,400 of a full day—a duration that could be measured using mechanical clocks.

This system, while practical, had its drawbacks. Physical objects are not perfectly stable—the metal meter rod could expand or contract slightly with temperature changes, the kilogram weight standard could change due to dust accumulation or loss of tiny amounts of mass over time, and even the second was not perfectly fixed, as Earth’s rotational speed varies slightly over time. While these changes were small, even minor fluctuations could introduce errors in scientific research and technological applications.

Recognizing these limitations, scientists in the mid-20th century decided to redefine measurement units based on fundamental physical constants—values that remain unchanged in nature. This led to the establishment of the modern International System of Units (SI) in the 1950s, a system that continues to be periodically refined and updated to this day.

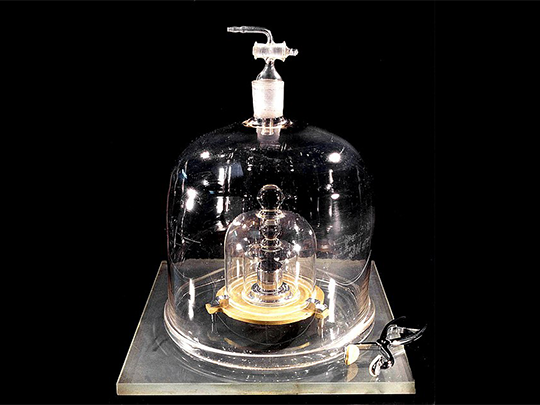

The SI system is based on seven fundamental physical constants, which define its seven base units. These constants—unchanging values based on the laws of nature—eliminate the problem of measurement units shifting over time. While a metal rod used to define a meter could expand or contract with temperature, natural constants, such as the speed of light, remain stable. The seven base units in the SI system are the meter, kilogram, and second, along with the ampere (symbol A – unit of electric current), kelvin (symbol K – unit of temperature), mole (symbol mol – unit of measurement for amount of substance), and candela (symbol cd – unit of luminous intensity). All other known units of measurement can be expressed using these units.

4 View gallery

The seven base units in the SI system are the meter, kilogram, second, ampere (the unit of electric current), kelvin (for temperature), mole (for the amount of substance), and candela (for luminous intensity)

(Photo: Shutterstock)

These seven units are defined by seven fundamental physical constants: the speed of light in a vacuum, the elementary charge (the charge of a single electron or proton), the Planck constant (which relates the energy of a photon to its frequency), the Boltzmann constant (which relates temperature to energy), the Avogadro constant (which specifies the number of constituent particles—atoms or molecules—in one mole of a substance), the hyperfine transition frequency of a cesium-133 atom (which defines the second, based on the radiation emitted during the transition of an electron in a cesium-133 atom from one orbital to another), and the luminous efficacy of a monochromatic light source at a frequency of 540 terahertz.

How can we use this system to determine the sizes of the units? Let’s take a look at some examples. The frequency of the light emitted during the hyperfine transition of a cesium-133 atom is 9,192,631,770 hertz, or a little over 9 billion cycles per second. In the SI system, one second is defined as the duration of 9,192,631,770 cycles of this radiation. This transition is measured by highly precise atomic clocks worldwide.

Similarly, the speed of light in a vacuum is 299,792,458 meters per second. Since we already know the duration of a second, we can define a meter as the distance that light travels in 1/299,792,458 of a second. Using the meter, second, and Planck constant, we can define the kilogram; using the second and the elementary charge, we can define the ampere, and so on.

At first glance, this method might seem overly complicated—it requires highly precise measurements of specific physical constants. Wouldn’t it be easier to simply measure a one-meter rod? While that approach has its merits, there are strong arguments in favor of the modern system.

First, these fundamental constants can be measured with unprecedented accuracy. The margin of error in their measurement is less than one millionth of a percent, making them exceptionally well-defined.

4 View gallery

The first cesium atomic clock, built in 1955, enabled the precise definition of the second using the new measurement system

(National Physical Laboratory Crown Copyright / Science Photo Library)

Second, while the process of measuring these constants is indeed complex, it ensures a fixed, rational, and consistent system—one that remains valid everywhere, whether on Earth, in space, or on another planet, and applies equally in the past and the future.

Finally, a consistent system of measurement is crucial in everyday practical applications. For example, internet speed relies on global communication networks, which depend on high-speed components operating with precise synchronization. This synchronization is made possible by the uniformity of units such as the meter and the ampere, shared by all components worldwide, ensuring seamless operation across all technological systems worldwide. Similarly, the SI system facilitates global commercial, technological, and scientific collaboration—and perhaps, one day, beyond Earth itself.